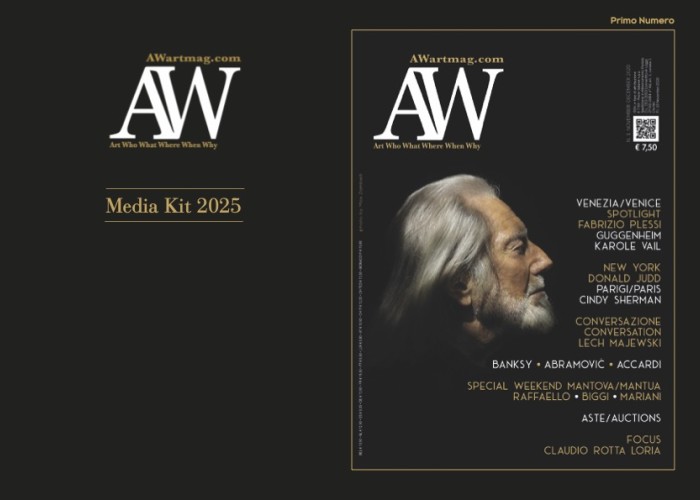

Barilli reflects on his long career

Literary and art critic, university professor and painter: he is a prominent figure in the Italian culture scene

The Bologna of the early ‘60s, the lively Bologna of Dozza, Lercaro, Morandi and Mandelli, as well as Anceschi and the Arcangeli (Nino the musician, Gaetano the poet, Bianca the painter who called herself Rosalba and Francesco the historian, known to his friends as Momi), was the right place and time to meet one of the three souls of Renato Barilli, precisely the art and literary critic. It happened to me while reading on the n.3/1960 of “Il Verri” his note on the 30th Venice Biennial. It opened on “the indecision of the jury, regarding the assignment of the international prize, between Fautrier and Hartung”, even though “the history and the value were decidedly on Fautrier’s side”.

There is always an artist in a critic and a critic in an artist

I had the opportunity to appreciate his role within the Gruppo 63 (of which he was a member) during the second convention held in Reggio Emilia at the beginning of November of 1964. In the following years, beyond the restless 1968, his going through books and paintings made me understand how Luciano Anceschi and Momi Arcangeli were the two specific references in Barilli’s critical history. A history that began of course, before “Gennaio 70, Comportamenti Progetti Mediazioni”, the exhibition held in the Civic Museum of Bologna in the first months of that year, which saw him being curator with Andrea Emiliani, Maurizio Calvesi and Tommaso Trini, which confirmed his mobile vision of art between open and closed shapes and cold informal and which, by increasing “the repertoire of ‘means’”, had allowed “some artists to experiment with an unprecedented one particularly in tune with the characteristics of an advanced electronic civilization’”.

1968 was an important year for me with the triumph of my beloved McLuhan

Reaffirmed two years later, in “Opera o comportamento” “something more, or at least different, from a pure and simple comparison between two currents or tendencies”, being commissioner of the Italian selection in the 36th Venice Biennial(we will find him again in the lagoon city among the curators of “Aperto 90” asking himself: “Towards a cold baroque?”) with Francesco Arcangeli and Marco Valsecchi; as well as in the International Performance Week which, from the 1st of June to the 6s 1 to 6, 1977, presented (with him, his students Francesca Alinovi and Roberto Daolio) the protagonists of the reappropriation of the body and the use of new audiovisual media, with Marina Abramovic and Ulay naked, and all of us passing among them to enter the Municipal Art Gallery of Bologna, and Hermann Nitsch and his Orgy Mistery and Theater in the deconsecrated church of Santa Lucia.

Throughout my life, next to my interest in art, there has always been an interest in literature

From that moment on, for Barilli there have been a long sequence of curatorships, among which, in the spring of 1980, “Dieci anni dopo - I Nuovi nuovi”, the exhibition with Alinovi and Daolio in the aforementioned Gallery that marked the beginning of a new artistic movement (the Nuovi nuovi, precisely) linked to the quote that is dear to postmodernism; then, still in the same location but with Franco Solmi, “La Metafisica: gli anni Venti (1980) and “L’Informale in Italia (1983), and then “Anniottanta” (1986) and “Anninovanta (1991), as well as “Il Nouveau Réalisme dal 1970 ad oggi” at Pac in Milan in 2008. He also wrote many books between art and literature including: “Dall’oggetto al comportamento. La ricerca artistica 1960-1970” (Ellegi, 1971), “Il ciclo del postmoderno. La ricerca artistica negli anni ‘80” (Feltrinelli, 1987), “Culturologia e Fenomenologia degli Stili” (Il Mulino, 1991), “La neoavanguardia

italiana. Dalla nascita del ‘Verri’ alla fine di ‘Quindici ‘” (Il Mulino, 1995), “A Map of the Arts in the Digital Age. Per un nuovo Laocoonte” (Marietti, 2019). In 2010, after having completed his long course of teaching/soul/method: Aesthetics, History of Contemporary Art at the University of Bologna as well as Phenomenology of Styles at DAMS, Barilli returned to his first love/ soul/method, painting, which, as he says, “I had practiced with commitment, graduating from the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna with masters such as Virgilio Guidi and Pompilio Mandelli in 1959, a year after taking a degree in modern letters,” recalling also the only personal exhibition (1962) at the Circolo di cultura. He proposes his works on several occasions, not least the exhibition “Visti da vicino” (2019) in the Gallery La Nuova Pesa of Simona Marchini in Rome, with tempera paintings depicting, in a clear informal derivation between stamps and tones, characters of the art world. Starting from a photo or a smartphone snapshot, in the continuation of his attention to new technological means that, on March 5, 2015, had determined the birth of “Pronto Barilli. Art, literature, current events: the blog of Renato Barilli”, the weekly appointment in three parts that renews his action of observer, scholar of the use of computers and militant critic. All of this is what brings me today to ask him these seven questions ranging from past to present times.

What was your relationship with Francesco Arcangeli?

I must point out that I was not a student of Francesco Arcangeli, but of his older brother, Gaetano, my literature teacher at the Galvani classical high school. I believe that if for my entire life, alongside my interest in art, there has also been an interest in literature, I owe it to him. On the other hand, I began to work in art at a very early age, almost as an enfant prodige, receiving a perfect technical education, culminating in my attendance at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna, and at the same time I graduated in modern literature. But certainly the contact with the great Momi was decisive, when he established himself n the early 50s. The whole of Bologna owes it to him if it was among the first cities in Italy to become aware of the Informal movement, through the famous essays by Arcangeli that appeared in “Paragone”. I also owe him the two greatest successes of my entire career as an art critic, having procured for me a university professorship in the history of contemporary art in 1972, and having invited me to participate alongside him in the Italian section of the Venice Biennial in 1972, where, like the naysayer he has always been, he supported the cause of the “work”, of painting, through his three “M’s”, Mandelli, Moreni, Morlotti, but he also opened up in the direction of behavior, entrusting me with the role of championing it.

What do you remember about your student Francesca Alinovi?

Francesca Alinovi was my best discovery among the students I have had in many years of teaching. I have to say that at the first meeting she was still lingering on old frontiers, but I soon convinced her to deal with Piero Manzoni and to follow me in every adventure of the most advanced ones, such as the performances of the 70s, the new-new ones of a little later, enterprises in which I was also joined by Roberto Daolio. She then took off to New York and came into contact with graffiti artists, ready to introduce them to us.

What is the role of art criticism?

Art is based on three factors, those who produce it, those who mediate by explaining it to the public, but also those who protect it, with the galleries and its market. These three factors must coexist in a healthy and physiological system. I must point out that one is not born belonging to one or the other of these roles. In this regard I use the simile of the fetus, undecided until the third or fourth month whether to become male or female, and there are also those who stop at an intermediate state. In the same way, we remain in an ambiguous and undecided zone until we opt for one or the other solution. And so there is always an artist in a critic, and vice versa, you cannot separate the two sides with an axe.

How much did 1968 influence Italian art in the ‘70s?

For me, 1968 was an important year because of the triumph of my beloved McLuhan with the imposition of electronics, of which he was a strenuous supporter. That technological revolution explains why, at that time, “representation” was abandoned, with the projection of images on a twodimensional support, in order to propose forms of direct intervention, installations, performance, and photography and television shooting as their substitutes.

Today, in what direction are Italian artists moving?

It seems to me that Italian artists are proceeding at a good pace in the same way as what is happening now throughout the world, where the historical differences that, for example, only enabled us Westerners to “represent” reality have disappeared. Now, in all countries, photography, video, installations, but also painting in an environmental dimension, such as wall painting or street art, are being used. This would be the infamous globalization, which, however, allows each ethnic group to recover its own roots, and an excellent synthesis between the global and the local, the glocal, to which we all contribute, is born. Also worth noting is the increasingly decisive role assumed by the female component, now almost equal in number to the exponents of the opposite sex.

After half a century, what can still be the uniqueness of the DAMS?

The DAMS is no longer unique. It was at the beginning when its founder, Benedetto Marzullo, had a great ministerial influence and had the requests of other universities to have it rejected, but nowadays this prohibition has completely fallen, and DAMS courses, or their equivalents with different acrostics, can be found in almost all the most important universities. However, the criterion of the three plus two degrees, with a first general and a second more specialized one, has caused a deep wound to the DAMS; at first they were of four-year duration, and obliged students to follow all the courses, now they are reduced to a single three-year period, since the two-year degrees, so-called magistral, imply a choice, one specializes either in art or in music or in cinema or in theater. Moreover, since there are three-year DAMS degrees everywhere, families force their children to attend the three-year degree at home, being willing to pay only for the two-year degrees, which are rarer and can only be found at the most important universities.

Returning to painting is a necessity; I feel the duty to recover one of my talents

Your return to painting: regret, remorse, or a necessity?

You say very well, my return responds to the three aspects you list: it is regret for the time I lost by sacrificing my undoubted vocation, it is remorse for having done so to the detriment of one of my components. It is also a necessity: before leaving this world, I feel the need to recover one of my gifts.