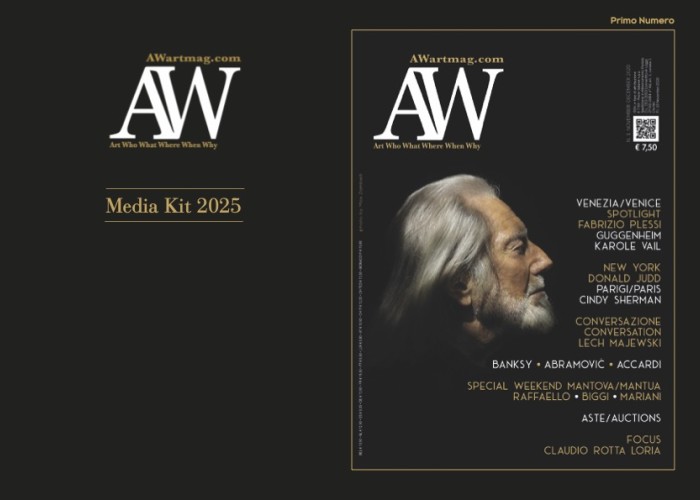

Considered the most extreme exponent of minimalism, Donald Judd pushed his pursuit of simplicity, elementary geometries, modulations, and mathematical progressions to the limit

His multifaceted career - he went from painting to criticism and then from criticism to sculpture, minimalism, and activism, with forays into architecture and design - is the core of the “Judd” exhibition that runs at the Steven and Alexandra Cohen Center for Special Exhibitions in New York until January 9. A simple title... Or a naïve one? A sharp provocation or a delightful paradox? After all, Donald Judd turned the impersonality of the artistic practice into one of the signature features of his work. In other words, unlike abstract Expressionists, he had no interest in expressing his ego or emotional, psychic, and artistic life. Why, then, should the first US retrospective dedicated to him in thirty years be called “Judd”?

Through this poor title, the curators want to let us catch a glimpse of the difficulties and real contradictions that unavoidably arise when talking about Minimal Art at large and Donald Judd in particular. Judd is considered by many to be the most extreme exponent of so-called minimalism, the one who most of everyone pushed to the limit the search for simplicity, elementary geometric shapes, modulations and mathematical progressions, and the pure materiality of the object. However, pushing to the limit also entails the risk of crossing it. This is the paradox in which Judd moves - in a more or less aware way. On the one hand, one would like an art object that refers to nothing outside itself, such as a metal parallelepiped; on the other, we should wonder if a metal parallelepiped can really be considered just a block of metal.

Through his specific objects he cultivates the utopia of sculpting a perfect identity

The specific objects (Judd’s geometric sculptures) aim to put an end to artistic illusionism; to every form of transcendence and hierarchy; to the relationship between model and copy, between the ego of the artist and that of the observer. So, there is - or should be - nothing beyond what we see and its simple but not so obvious presence. Tautology, perhaps solipsism - because language itself might be nothing more than an illusion, a conversation between deaf people, a misunderstanding. In short, with his specific objects Judd cultivates the utopia of sculpting a perfect identity, in which a metal parallelepiped is nothing more than a metal parallelepiped. Here, however, comes someone who spoils everything, remarking that that parallelepiped, after all, looks like a tomb.

JUDD

Museum of Modern Art

New York

Until 9/01