Paris • Spotlight on Baselitz at the Pompidou Center

The works created over the course of 60 years are gathered in a strictly chronological way

The spaceship, designed by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers and inaugurated in 1977 in the heart of the historical market of Les Halles in Paris, has proven to be one of the most suitable venues for hosting large exhibitions over the years. And it is a retrospective in full swing - as the title “Baselitz. The retrospective” - which unfolds in the large space of the Georges Pompidou Center, gathering in a strictly chronological way the works made by the master over the last six decades.

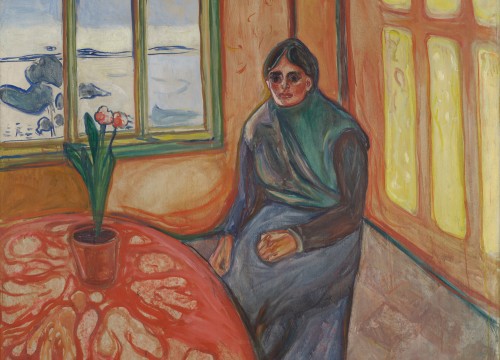

Baselitz rejected his first name Hans Georg Kern and adopted his current name taken from his birthplace

In the exhibition we meet the “wild” works of the early ‘60s related to the Manifesto Pandemonium (Pandemonium Manifesto) published in ‘61 - when he rejected the first name of Hans Georg Kern and adopted the current one taken from his place of birth. The Heroes Series, the Fractured compositions, the large-format paintings of the so-called Foresters up to the beginning of the production of the famous upside-down paintings of ‘69. In the middle, in ‘63, the scandal caused by the paintings exhibited at the Werner & Kats Gallery in West Berlin (which led to the seizure of The Big Night Down and Naked Man for obscene content) and, in ‘65, the six-month stay at Villa Romana, in Florence - where from ‘76 he set up an additional atelier and deepened his knowledge of Pontormo, Rosso Fiorentino and Parmigianino, to whom he will remain linked throughout his career as evidenced by the paintings on display.

The exhibition offers the opportunity to investigate the nature of the works and the linguistic evolution that led him to create a harmonious coexistence between abstraction and figurative art. From the itinerary of the exhibition and from the rich didactic and informative apparatus, Baselitz’s affinities with artists such as Picasso and Giacometti in the early ‘60s, without neglecting the performances of Beuys and the omnipresent stylistic shadow of Die Brücke, are evident, passing through Italian Mannerism. But, above all, it is the source and the engine of Baselitz’s articulated research that reveals itself to the visitor: those foundations supporting more than 60 years of a style that led the historian Andres Franzke in 2013 to declare him the most influential artist of his time together with Jackson Pollock and Philip Guston.

It is he himself to close and summarize his creative path: “I was born in the middle of a destroyed order, a ruined landscape, a ruined people and nation. I didn’t want to introduce a new order. I had seen enough of what were called new orders. I was forced to question everything (...) I have never possessed either the sensibility or the philosophical knowledge of the Italian Mannerists. But I am a mannerist, in the sense that I feel the need to deform things.